WASHINGTON, Jan 13 — He has toppled Venezuela’s leader, vowed to control its vast oil reserves and threatened other Latin American countries with similar military action. He has talked openly about annexing Greenland, even by force.

And, beyond the Western Hemisphere, he has warned Iran that the United States (US) could strike it again.

Ushering in the new year with a flurry of aggressive moves and fiery rhetoric just days before the first anniversary of his inauguration, President Donald Trump has taken a wrecking ball to the rules-based global order that the US helped build from the ashes of World War II.

That has left much of the world reeling, with friends and foes alike struggling to adjust to what seem like altered geopolitical realities. Many are uncertain of what Trump will do next and whether the latest changes will be long-lasting or can be undone by a more traditional future American president.

“Everyone expected Trump to return to office with bluster. But this bulldozing of the pillars that have long undergirded international stability and security is taking place at an alarming and disruptive pace," said consultancy Global Situation Room's head Brett Bruen, who formerly served as foreign policy adviser in the Barack Obama administration.

Spheres of influence

While much is still unclear, Trump, in a matter of months, has demonstrated a taste for exercising raw American power, as he did with the bombing of Iran’s nuclear sites in June and the January 3 attack on Venezuela.

And he has signalled that he may intervene again, especially in the Western Hemisphere, where he has vowed to restore US dominance, despite having campaigned on an 'America First' agenda of avoiding new military entanglements.

This assessment of Trump's shakeup of the global system draws on interviews with more than a dozen current and former government officials, foreign diplomats, and independent analysts in Washington and capitals around the world.

On the global stage, he is resuscitating what much of the international community had long spurned as an outdated worldview: spheres of influence carved out by the big powers.

The inspiration is the 19th-century Monroe Doctrine, which prioritised US supremacy in the Western Hemisphere and which Trump has embraced and reworked into the 'Donroe Doctrine'.

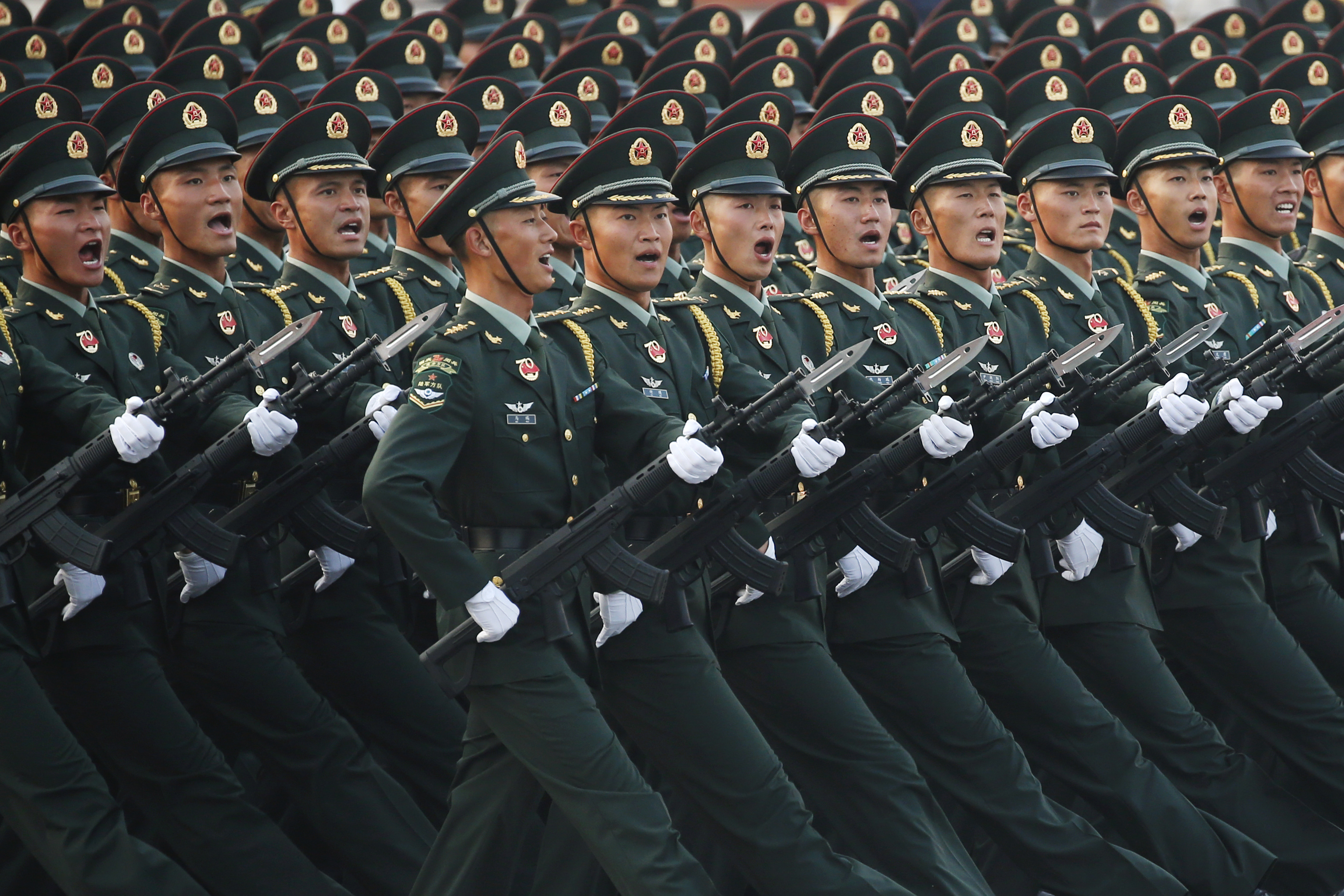

Experts say that while the revival of this playbook may have unnerved some US allies, it could also serve the interests of Russia, locked in a war in Ukraine, a former Soviet republic, and China, which has long had its sights set on Taiwan.

Following the US attack on Venezuela and Trump’s transparent play for the OPEC states' vital resources, some of America’s staunchest allies have shown increasing concern about the undoing of the world order.

At stake is an international system that has taken shape over the past eight decades, largely under US primacy, and though subject to occasional reversals, has helped stave off worldwide conflict. It has come to be based on free trade, the rule of law, and respect for territorial integrity.

A White House official said the policies Trump is pursuing, including a heavy focus on the Americas, the display of military might, a border crackdown, and the sweeping use of tariffs, are what he was elected to do, and "we are seeing world leaders respond accordingly."

Influential White House adviser Stephen Miller appeared to summarise the administration's worldview when he told CNN on January 5: “We live in a world, in the real world ... that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power."

Europeans, already shaken by doubts about Trump’s willingness to defend Ukraine against Russia, have spoken out more openly in recent days, especially over his fixation with Greenland, an autonomous territory of Denmark, a fellow Nato member.

Last week, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier accused the US of a “breakdown of values” and urged the world not to let the international order disintegrate into a "den of robbers.”

On Friday, Trump said that the US needs to own the Arctic island to prevent Russia or China from occupying it, though Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen has warned that a US move to take Greenland would mean the end of the transatlantic alliance.

Amid growing unease, some European leaders have suggested that Nato deploy forces in the Arctic to address US security concerns.

Safeguarding their interests

Even before the latest developments, some US allies had begun taking steps to safeguard against Trump’s sometimes erratic policies, including growing European efforts to boost their own defence industry.

Trump also has stirred anxiety among Washington’s Asian partners.

Former defence minister and influential Japanese ruling party lawmaker Itsunori Onodera wrote on X (formerly Twitter) that the US operation in Venezuela was a clear example of “changing the status quo by force.”

Trump’s berating of European allies and seeming tilt toward Russia last spring prompted a contingent of senior Japanese lawmakers to consider that the only nation to have been attacked with atomic bombs might have to develop one of its own.

In South Korea, progressive Rebuilding Korea Party lawmaker Kim Joon-hyung said that Trump’s actions in Venezuela “opens a Pandora’s box where the strong can use force against the weak.”

In contrast, former Japanese prime minister Shigeru Ishiba told Reuters that he did not see Trump’s Venezuela action as an “earth-shattering development” for the world order, though he questioned whether Trump’s increased focus on the Western Hemisphere was a message that “Europe, you are on your own.”

Most friendly governments have had a largely muted response to Venezuela, reluctant to antagonise the US President.

“Publicly scolding Trump is not going to help achieve our aims,” said one United Kingdom official, speaking anonymously.

Leftist-governed Mexico was quick to criticise the US ouster of Venezuela’s authoritarian socialist leader Nicolás Maduro, but with so much at stake in relations with its northern neighbour, a senior Mexican official said it “will not go beyond publicly condemning the use of force."

Last week, in an interview with the New York Times, Trump, who has threatened unilateral military action targeting drug cartels inside Mexico and Colombia, said that his authority as commander in chief is constrained only by his “own morality,” not by international law.

A new imperialism?

While critics accuse Trump of a new imperialism in Latin America, his defenders say it is long overdue, especially given China’s economic and diplomatic inroads in the region.

The White House official, speaking anonymously, said that Trump was "rightfully restoring American influence," especially by taking out Maduro, whom he had accused of "poisoning" Americans with a flow of illegal drugs and sending Venezuelan migrants to the US.

“While the administration’s actions in Venezuela have shocked the world and sent a strong message to US rivals in Beijing, Moscow, Havana, and Tehran, they are likely only the starting point for a longer-term and more comprehensive reappraisal of US core interests in the hemisphere,” said think-tank Atlantic Council senior fellow Alexander Gray, formerly a foreign policy adviser in Trump’s first term, on its website.

Yet Trump's approach carries risks for the US, as analysts have noted that key regional players such as Brazil could be pushed even closer to China as they hedge their bets against Trump's pressure.

Most unsettling for US allies has been Trump’s focus on Venezuela’s oil as a driving force behind the removal of Maduro. Washington has left the deposed president’s loyalists in power for now while strong-arming them to grant US companies privileged access.

Experts have warned that the use of US power without any reference to international norms could embolden China and Russia to intensify coercive moves against their own neighbours. But the White House official countered that US adversaries had "undoubtedly taken note of the President's strength."

Shanghai's Fudan University international affairs expert Zhao Minghao said the US had “hyped up the notion of a ‘China threat’ in Latin America." Soon after taking office, Trump spoke of taking back the Panama Canal and pressed the Panamanian government to reconsider Chinese-run facilities near the strategic waterway.

But he also noted that Trump appeared supportive of the major powers’ spheres of influence, an approach that many believe appeals to Beijing.

The prevailing view in Russia is that the US attack on Venezuela, including taking Maduro to New York to face “narco-trafficking” charges, was a pure power play.

"That Trump just 'stole' the president of another country shows that there is basically no international law; there is only the law of force. But Russia has known that for a long time," former Kremlin adviser Sergei Markov told Reuters.

Trump’s appetite for further foreign military action may continue for targets well beyond the Western Hemisphere.

Even amid the fallout over Venezuela, he has threatened to intervene on behalf of protesters in Iran, where Muslim clerical rulers are facing one of the stiffest challenges to their control since the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

On Sunday, Trump told the media on the Air Force One presidential aircraft that he was weighing possible responses, including military options.

"We may have to act because of what is happening," he said.