KUALA LUMPUR, Nov 2 — Never before in the new millennium have so many world leaders gathered in Malaysia, including the heads of major Global South economies like Brazil and Canada.

Even the visit by President Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa last week marked only the second by a South African leader, following Nelson Mandela’s visit 28 years ago in 1997.

With such diverse top leaders and officials converging here last week — 30 in all — Malaysia is charting a steady course to deepen economic ties with both longtime allies and emerging partners.

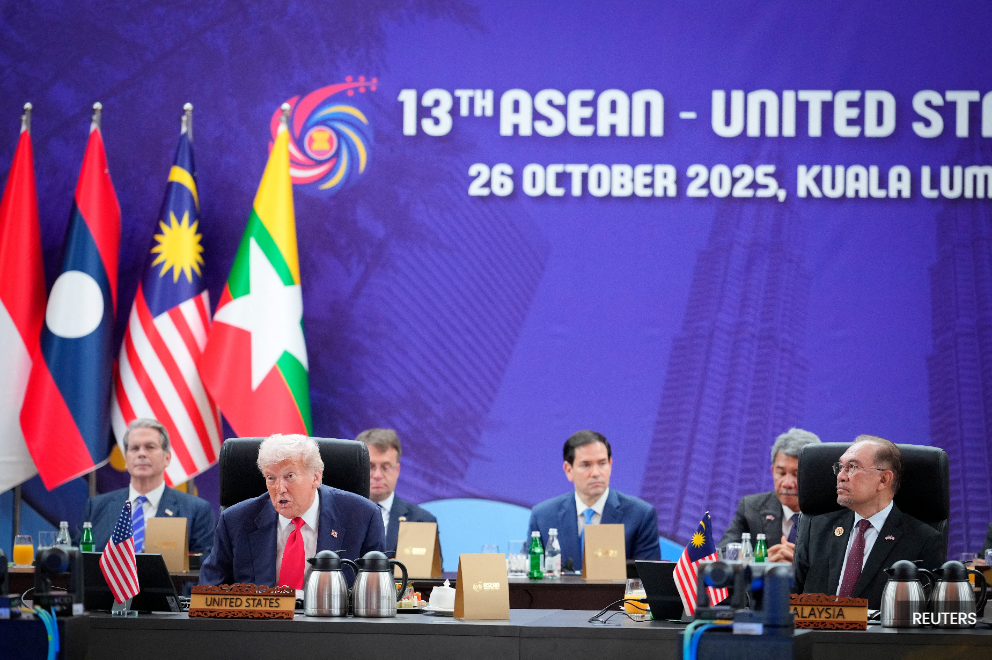

Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim should be commended for bringing United States (US) President Donald Trump to Malaysia, who is undoubtedly the man of the hour in the global trade debate. For a highly export-oriented nation, Malaysia is 'walking the talk', having to contend with unpredictable dynamics of international business relations and trade.

Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Kedah's Administrative Science and Policy Studies Faculty senior lecturer Tunku Nashril Abaidah said Malaysia’s policy of engaging with all major economies is a hallmark of its non-aligned and pragmatic foreign policy tradition, which has contributed to its economic resilience.

In managing high export costs due to the imposition of 'Liberation Day' tariffs by the US, the panacea, as Anwar has consistently pointed out, is for countries to realign supply chains, penetrate new markets from evolving South-South partnerships, and most importantly, keep the line of communication open with both friend and foe.

Global trade is volatile, so much so that it is difficult to predict trends over the next six months. Trade remains fluid, and countries continue to recalibrate their economic stance almost daily.

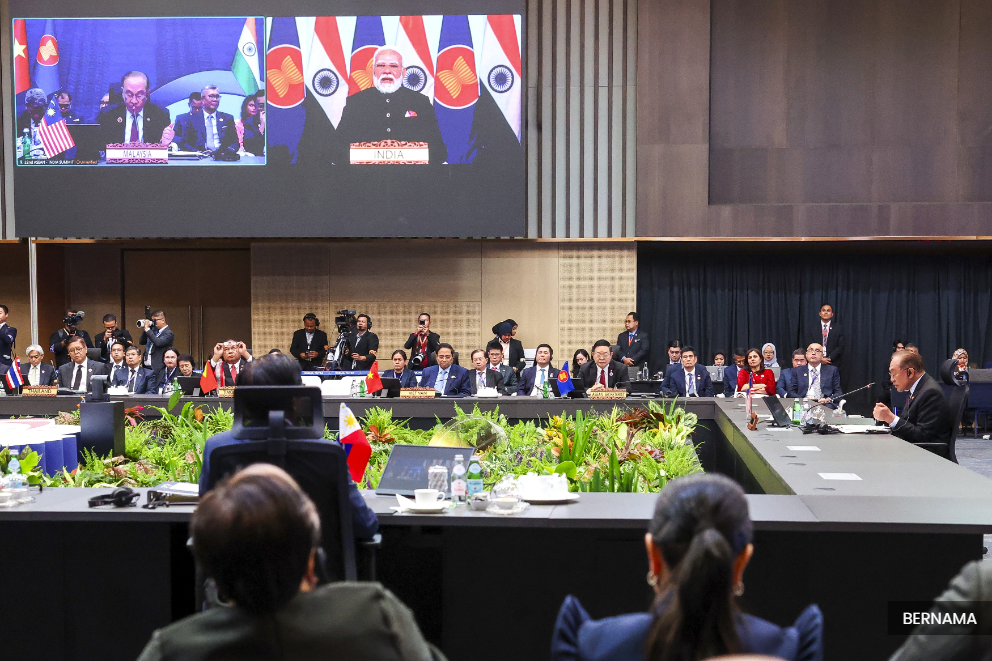

At the recently concluded 47th Asean Summit and Related Summits, chaired by Malaysia, the extended invitations to Brazil, South Africa, and Canada showed that Malaysia went beyond the familiar optics of diplomatic handshakes.

While everyone’s focus was on the US and China at the KLCC, where the summits were held, Putrajaya was spreading its wings to engage emerging powers and increase South-South cooperation to tap into trade and investment opportunities. Malaysia is expanding its trade network, making the country more conducive to welcoming foreign businesses by portraying the country as an open economy and one that is not confrontational but accommodating.

It is heartening to note that the Malaysian way is also the Asean way, realising that coming together as a united bloc is the path to regional prosperity.

The bloc’s trade has skyrocketed, with the Asean-China Dialogue Relations, established in 1991, having grown into the region’s largest economic partnership, with trade reaching US$772.2 billion (RM3.24 trillion) in 2024 and about US$684.7 billion (RM2.87 trillion) in the first eight months of 2025 alone.

The Asean-US dialogue (established in 1977) saw trade in goods and services totalled US$571.7 billion (RM2.39 trillion) in 2024, while Asean-Japan (1973) recorded US$236.4 billion (RM992.2 billion) in 2024, and ties with South Korea (1989) recorded US$465.7 billion (RM1.95 trillion) in trade last year.

Beyond East Asia, the Asean-Canada partnership, established in 1977, reached US$23.5 billion (RM98.64 billion) in merchandise trade, and the newest engagement with Brazil, formalised as the Sectoral Dialogue Partnership in 2024, posted US$33.3 billion (RM139.7 billion) in trade for 2023, signalling the bloc’s growing South-South economic linkages.

“Sustaining that resilience in the long term will depend on how effectively Malaysia adapts this engagement strategy to evolving global power dynamics and internal economic realities,” Tunku Nashril told Bernama.

By maintaining broad engagement, Malaysia avoids the structural vulnerability that comes with overdependence on a single power.

“Its diversified portfolio of trade and investment partners, such as China, the United States, Japan, South Korea, the European Union, and increasingly, India and the Gulf states, cushions it against global shocks. When one market slows or becomes politically contentious, others can offset the impact.

"This diversification has been a vital source of economic stability, particularly during episodes such as the US-China trade war or regional currency volatility,” he said.

Moreover, this balanced diplomacy allows Malaysia to extract benefits from competing powers without being drawn into their rivalries.

“For instance, Malaysia gains infrastructure investment from China’s Belt and Road Initiative, while also accessing advanced technology and markets through US and European partnerships. In essence, Malaysia turns great-power competition into a source of economic opportunity.

"A sophisticated form of strategic hedging within a cooperative framework,” Tunku Nashril said.

However, he cautioned that this approach is not without its strains, as maintaining “equidistance” requires delicate balancing.

“Malaysia must ensure that neutrality does not translate into passivity. As geopolitical competition intensifies, especially between Washington and Beijing, the space for manoeuvring may narrow.

"Pressure to take sides could increase in areas such as technology regulation, supply-chain security, or defence cooperation," Tunku Nashril said.

Domestically, Malaysia must also upgrade its economic fundamentals, focusing on governance, innovation capacity, and human capital to remain an attractive partner. He added that diplomatic neutrality alone cannot guarantee resilience if the domestic economy lags in competitiveness.

When asked how an open policy could protect micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) from larger foreign competitors and market distortions, Tunku Nashril said the focus should be on selective liberalisation, with efforts to strengthen SMEs through capacity building and fair trading practices.

For example, when participating in agreements such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, Malaysia negotiated transition clauses for sensitive sectors, such as agriculture and manufacturing. This ensures that domestic firms have time to upgrade capacity before full exposure to global competition.

Malaysia’s balancing act reflects strategic maturity by keeping diplomacy open, trade diversified, and partnerships expanded, in the process creating crosscurrents which show Putrajaya is not merely weathering the storm, but charting the course ahead in a definitive direction.